By Maggie Stack, NHS Buchanan/Burnham Intern 2014

The midshipmen of the United States’ navy were caught in an uncomfortable situation in the antebellum period. The system for their training and education, modeled after Britain’s Royal Navy, had not changed from the Navy’s reconstitution in 1794. Midshipmen went to sea to receive on-the-job training, working as junior officers integral to the running of the ship. They were supposed to receive an education as well, and many naval ships carried school masters for this reason. Although this system had apparently worked for several decades, many officers and would-be-reformers felt that this system was failing the midshipmen. First, they felt that midshipmen were morally and physically endangered by life at sea. Second, they felt that midshipmen were not receiving the education they needed to become effective officers in the rapidly changing 19th century.

Charles Hunter had a proverbial front-row seat from which to observe this failing institution. The grandson of Dr. William Hunter, he went to sea aboard the USS Potomac, an American frigate, in August of 1831, at the age of 19. His unusually detailed personal journals chronicle his life aboard ship and the problems he faced there. Education became a subject of particular frustration for him. His journal provides a vivid illustration of the problems with education at sea, and the issues naval reformers of the 1830s and 1840s wanted to address.

One of the first challenges facing Hunter and his fellow midshipmen was the school and school master. It was not until a few weeks into the voyage, on September 12th 1831, that he noted a crude school-room had been created for the use of the midshipmen. Later in the voyage, on 16 December 1831, Hunter noted, with apparent chagrin, that, “in the corner of our school is kept the Commodores milch[sic] goat and her kid which makes considerable noise.” The lack of space available to the midshipmen for their school indicated where the education of midshipmen ranked on the list of priorities aboard ship.

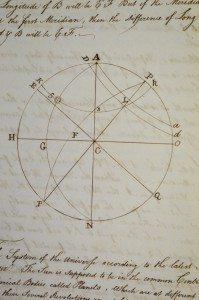

A detail from an 18th-century workbook by Newport teacher William Engs, showing navigational techniques based on observance of the position of particular celestial bodies (sun, planets, etc). From the NHS collection.

In Hunter’s opinion, the school master matched the school-room – being referred to as “one of the dullest of persons,” on 28 November 1831, or, more scathingly, on 16 December 1831, “a dull religious book learning young man who does not care at all whether we learn anything.” In the same entry, he rails that the school master has not held classes or instructed the midshipman in any way – leaving the midshipmen to read novels or write letters instead or pursuing their education. Naval school masters were not assigned to every ship, and, even when they were, had a reputation for ineffectiveness. Some of that may have been due to their failings, but part of the problem, as seen by reformers, was that midshipmen were treated as officers first and students second, leaving the school masters to scrape together classes with whoever was not on duty and could be coerced into attending classes.

In light of the lack of study aboard the Potomac, Hunter set out plans of education for himself. Early on, on 9 November 1831, he says that he “began to translate a history of France in French, which I suppose will take me a year. I translate about a page and a half every day. I also have begin to look over Algebra and have taken Calculus[?] from which I do 6 or 7 sums every day.” Later entries note the books he reads, the mathematical problems he undertakes, or the navigational texts he studies. Hunter’s studies, however, usually backslid. He later notes, on 13 January 1832, “sometimes I write a Spanish exercise but I pay but little attention to it at all,” or on 5 March 1832 that, “I pay little or no attention to mathematics.”

Hunter’s experiences illustrated why many reformers wanted to take midshipmen off naval ships and educate them ashore. Education of midshipmen afloat was too frequently not a priority; there was no time devoted to teaching midshipmen foreign languages, composition, mathematics, or anything not related to the day-to-day operation of a ship at sea. Reformers argued that these topics were important for midshipman. Political, technological, and social developments, as well as the demands of a changing naval service, necessitated that midshipmen’s education be better enforced and more widely construed. Within 15 years, in the United States, these demands would lead to the establishment of the Naval Academy at Annapolis – although too late for Charles Hunter.